By December 1914, four months after the start of World War I, the “Race to the Sea” was complete, and two parallel lines of trenches ran from the North Sea to the border of Switzerland. The devastating effects of modern warfare were becoming alarmingly apparent, and some, such as Pope Benedict XV, called for a truce between the warring countries. But as we know, the call for a ceasefire went unheeded, and the war would continue for four more years.

However, that first Christmas on the Western Front saw a number of spontaneous temporary ceasefires among the men on both sides of No Man’s Land.

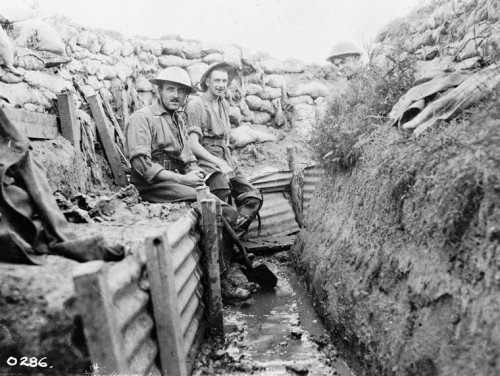

In the days leading up to Christmas, German and British troops received a number of care packages, both from home and from their governments. German soldiers decorated their parapets with candle-lit Christmas trees and sang carols, which could easily be seen and heard by the British troops, who were sometimes no more than 30 yards away. The trees became a conversation piece between the trenches. As the men spoke of Christmas, mutual goodwill led to carol singing, and in some areas, German and British troops actually met in No Man’s Land (at this point not the shell hole laden muddy nightmare it would later become as the war dragged on). There they exchanged presents (items taken from their care packages), and in some cases, buttons from each others’ uniforms as a type of souvenir. There was even an instance of a soccer game that took place between the two sides.

In all, roughly 100,000 men participated in this unofficial truce. It is important to note that this number mostly consisted of German and British troops. The French and Belgian soldiers were not as involved because at this point their land was occupied by the Germans, and any Christmas feelings of goodwill were overshadowed by this fact.

In most cases the men did not receive any discipline for this fraternization. This was due to the mixed reaction by both the British and German commanders when they heard the news. Some made clear their disapproval of such actions and the dangers that could come from interacting with the opposing side. Others did not see any major harm coming of the impromptu ceasefires, and felt that it might give their troops time to strengthen their trench structures, since they did not have to worry about being picked off by snipers or shell fire from the opposing side for a few days.

Some of the ceasefires ended with the close of Christmas Day–though a few lasted until the start of the New Year. And in some sectors no truce took place at all, providing no respite from the routine of war.

Evidence of Christmas truces in 1915 and 1916 were also recorded. Private Ronald MacKinnon, a 23 year old from Canada, wrote a letter home about Christmas on Vimy Ridge in 1916:

“I had quite a good Xmas considering I was in the front line. Xmas eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Xmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars.”

Private MacKinnon was killed four months later during the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

After 1916, the armies on both sides made a concerted effort to prevent further fraternization with the enemy. They scheduled bombardments to take place on Christmas Eve so the opportunity to share Christmas tidings would be impossible. Troops were also shuffled around to different sectors along the Front so that they never became too friendly with the men in the opposite trenches.

Today, the Christmas Truce of 1914 has become legendary. It gives us a bit of hope for humanity, knowing that even during the horrors of World War I, men from both sides were willing to put their guns aside for a day and offer goodwill towards men they were told to hate, to shoot, to kill.

Sources: First World War.com, Wikipedia

For more, check out this YouTube clip from a PBS documentary, featuring the Christmas Truce of 1914: